Quartered,

Flipped, and Rotated

An Installation by Devorah Sperber

Curated by Patterson Sims,

Director MAM

Montclair Art Museum, Montclair, NJ

October 9, 2004- May 8, 2005

Essay

by Patterson Sims

*The artist's quotes and statements below came from a series of e-mail exchanges and conversations in June and July 2004 between the artist and Patterson Sims, Director of the Montclair Art Museum and curator of the exhibition.

Vinyl wall covering with five mounted panels of chenille pipe cleaners, and plastic mesh

*I am interested in the link between art and technology, how the eyes prioritize, and reality as a subjective experience vs. an absolute truth. As a visual artist, I cannot think of a topic more stimulating and yet so basic, than the act of seeing--how the human brain makes sense of the visual world. -Devorah Sperber, 2004

Intrigued by art's capacity to unite seeing and

knowing and drawn to labor-intensive projects, the New York artist Devorah

Sperber has created since 1999 a fascinating series of large-scale installations

and multi-part works. Sperber's recent installations use pixel-based,

photographic images in formats that fluctuate between representation and

abstraction. Mixing conceptualism with sensuous, physical materiality,

her art is a product of a honed technical and scientific mind, formidable

sculpture and fiber-making skills, and an omnivorous sensibility. Sperber

utilizes digital technology to create high-tech works, but conspicuously

simplifies technology by utilizing mundane materials and hands-on assembly.

Work station where Devorah Sperber (above) and assistants assembled the five chenille stem works for the installation.

Born in 1961, Sperber was the youngest of her immigrant parents' three children, all daughters. Her father was German/Polish and her mother was German. A Jewish Holocaust survivor, her father, with his mother, came to the United States in 1949. Sperber's parents met in Germany in 1954 when her father was stationed there for his U.S. military service. Born and raised in Detroit, Michigan, at the age of ten Sperber and her family moved in the aftermath of the Detroit riots to Denver, Colorado. Her parents worked hard to build the family's successful businesses. They continued to maintain their insulation company in Detroit for several years as they established a bigger, related business in Denver that manufactured equipment to install her father's company's patented processes. Her father was, in the artist's words "very creative and thought out of the box"; Sperber equally prized her mother's "intuitive understanding of aesthetics" and her willingness to do whatever it took to "get the job done."

Throughout high school and early college, Sperber

assumed she would go into business. She worked after school in the production

end of her father's assembly shop. From 1979 to 1981 she attended the

Art Institute of Colorado in Denver. In 1985 she transferred to the city's

Regis University to pursue a bachelor's degree. By the time she graduated

summa cum laude from the University's Regis College in 1987, her interest

shifted from studying advertising and graphic design ("art as business")

to fine art. Her early artwork took the form of stone sculpture. She carved

expressionist, figurative works that jump-started her career when she

was asked, shortly after graduation, to include her stone sculptures and

their related bronze castings in a nationally circulated exhibition on

the Dutch Holocaust victim Anne Frank. Through the Anne Frank exhibition

she met Bruce Dobozin, an allergy and immunology specialist in New York.

A year later she moved to New York City to make her art and live with

Dr. Dobozin. They married in 1992 and live in New York City and Woodstock,

New York. In New York City she realized that it was confining and not

practical to be a stone carver. She wanted to increase the scale of her

work and began to use other, lighter materials such as cast hydrocal,

which could be replicated and grouped to create large installations. Some

of these quasi-figurative groupings were installed in front of digitally

composed images derived from computer-generated sources.

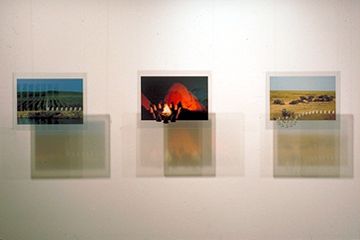

Humanity--And How We Got This Way, installation

view

Humanity--And How We Got This Way, installation

view of digital prints

The pixel components of these computer-generated images fascinated Sperber, and she searched for ways to combine pixel-based formats with sculpture. When viewing the Chuck Close retrospective at The Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1998, she realized that Close's use of analog photography-based processes for his paintings might methodologically be translated into using pixel-based structure for sculptural installations. Seeking a readily available, mass-produced "pixel-like" component, she first turned to spools of sewing thread and for her recent work has used chenille stem/pipe cleaner elements. The curved shape and wide spectrum of colors of the thread spools (which read at any distance as rectangles) were perfectly suited to become the pixilated digits of color of her sometimes curved natural or landscape vistas. These landscape subjects derived as much from her missing the out-of-doors and picturesque Colorado life as her fascination that the satiny spools of thread could be turned into building blocks for panoramic views of nature.

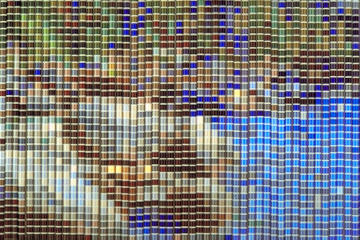

Reflections on a Lake, detail view of

thread spools

Reflections on a Lake, detail view of

thread spools reflected in convex mirrors

Her natural panoramas indivisibly wed art and science, clear depiction and ambiguity, and technology and craft. From these initial nature-based works and a more recent, continuing series of old master and contemporary art translations made of chenille stems, Sperber's pixel-based art has revolved around the scientific concepts of fractals and neurological priming. Fractals are the repetition of microcosmic to macrocosmic patterns, which cause the viewer to see and then lose sight of the parts that make up the whole. They define the visual seduction of her pieces. Neurological priming, the various means that continuously focus, filter, shift, and correct the coordination of sight and cognition, has added layers of ambiguity. Even as the scale of her works has grown, Sperber continues to work in small studio spaces. To compensate for the small size of her studio spaces in relation to what is produced there, she reverses binoculars and, standing outside the entries of her studio spaces, looks through their far end to reduce and compact the scale of her works in progress. Though not employed for the viewing of this installation, both in the making of and incorporated into her installations for viewers to see her pieces, Sperber has frequently used binoculars or such other optical aids as concave mirrors, silver oculus balls, polished stainless steel cylinders, and clear acrylic viewing spheres to condense and compact the expanse of her pieces.

Virtual Environment 1, installation view at SECCA,

20,000 spools of thread, silver oculus balls

My interest in the connection between art and technology evolved from my own working processes, which utilize technologies of our era--the computer, optical devices, and mass-produced objects.

I am interested in merging art and science as experiential components vs. intellectual concepts and utilize the element of surprise/temporal lobe activation - perhaps best described as the "WOW" experience, which occurs when the external world does not jive with the brain's inner expectations

Although the initial idea to use optical devices was a solution to the problem of not being able to step back far enough to see the large scale works in my small studio, I became intrigued by how optical devices cause individual units to coalesce into recognizable images in a dramatic way. Instead of an image gradually emerging, like a Chuck Close portrait, optical devices offer two distinct "realities" --one totally abstract and the other fully representational. This shift in perception functions as a dramatic mechanism to present the idea that there is no one truth or reality, emphasizing subjective reality vs. an absolute truth.

When Sperber first visited the Montclair Art Museum in the spring of 2002 to discuss an exhibition in the Blanche and Irving Laurie Foundation Art Stairway she decided to create a new, site-specific work. Her encounter with the Museum's well-known and iconic Edward Hopper painting, Coast Guard Station, 1929 became the catalyst later that year for a whole new series of pieces based on other artworks. At the Museum she was also drawn to the Museum's extensive collection of Native American textiles and basketry and considered ways to interconnect their craft and tactility to the Hopper painting; she sought to bridge the Museum's American and Native American holdings. Though it initiated the new series, Quartered, Flipped, and Rotated took two years to be realized. In the interim Sperber created pieces composed of chenille stems and other media based upon both well-known and less typical paintings of Jackson Pollock, Chuck Close, Hans Holbein, Salvador Dali, and Jan Vermeer. Other than Jackson Pollock, whose intuitive replication of fractals predated science's discovery, all these artists were profoundly influenced by the new technologies and scientific ideas of their eras.

My consideration of a Pollock drip painting as subject matter began with my interest in his ability to produce high ratios of fractals before fractals had even been recognized as existing. Pollock was intuitively seeing and recreating the natural world more accurately than the finest landscape painter. As he is purported to have said:" I am not reproducing nature, I am nature."

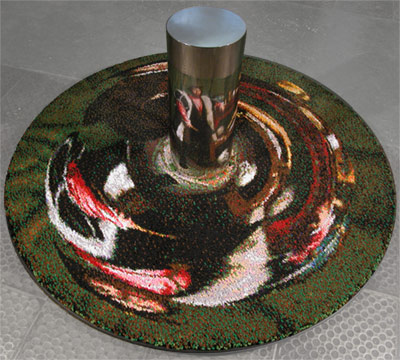

Shag Rug 165,000 (After Pollock),

installation view at Jack The Pelican Presents

I also liked the contrast of constructing an abstract expressionist work utilizing the most mundane, non-expressionist processes possible - deconstructing and recreating the imagery as pixels on the computer and then inserting 165,000 chenille stems by hand, one stem at a time, into foam board. Also recreating Pollock's Autumn as a "shag rug" and placing it back on the floor brought the imagery back to the way Pollock saw it from above while painting with his large canvases on the floor. I also constructed a series of reduced scale works based on the same drip painting, which through incremental reductions in resolution/scale dissolved into abstractions that pose the question: "At what point is the image no longer Autumn Rhythm?"

Shag Rug (After Pollock) Series, installation

view at Kohler Art

Center

The series After Chuck Close, 2002 expanded this inquiry into incremental reduction of resolution and scale; the largest work was a six by six foot rendering of a single "cell" of the Chuck Close self-portrait and the smallest work consisting of one chenille stem inserted into the wall. With each work in the series being incrementally smaller, one would expect fewer units/chenille stems to result in lower resolution and thus lower image quality. However, because the smaller works also contained an incrementally greater number of cells from Chuck Close's self-portrait, the imagery gradually became more recognizable peaking at 2'x2'. The works measuring 1'x1' and smaller were based on the same number of cells as the 2'x2' work, and thus behaved in the usual way with less units/chenille stems equating to lower image resolution all the way down to the smallest work consisting of a single chenille stem.

After Chuck Close, installation view at DAC

A neurologist pointed out to me that the series functioned as a neurological primer, literally priming or teaching the brain to make sense of visual imagery which is only recognizable when seen in the context of the greater whole

Two works, based on Hans Holbein's painting The Ambassadors, 1533, titled After Holbein, 2003-04, utilized his adaptation of anamorphic perspective, a mathematical technology invented by Leonardo da Vinci. I deconstructed, digitally morphed, and reassembled Holbein's imagery into two new anamorphic rug-like sculptures. Constructed from thousands of chenille stems, the images are only visible when seen reflected in a cylindrical mirror or from a precise location.

After Hobein, installation view

at McKenzie Fine Art

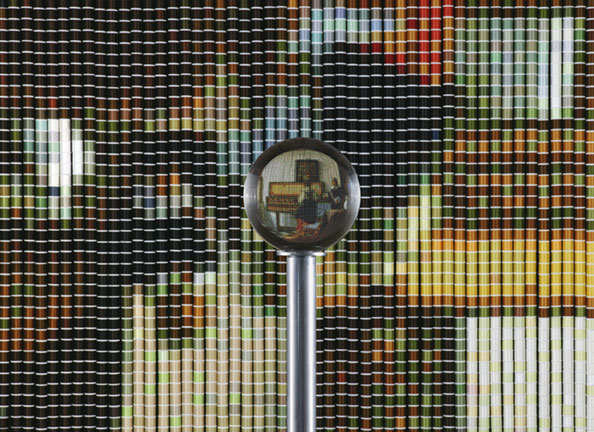

A strong case has been made that Jan Vermeer used a camera obscura as a tool to draft many of his compositions. In my four After Vermeer, 2003-04 works, based on Jan Vermeer's The Music Lesson, I transformed The Music Lesson into four circular works - one 8x8 foot work constructed from thousands of spools of thread and three 12x12 inch works constructed from thousands of 1" lengths of thread. Clear acrylic spheres, placed in front of the works, reduce and rotate the imagery 180 degrees, resulting in images similar to what Vermeer saw projected inside his camera obscura.

After Vermeer, detail view of

thread spools and acrylic viewing sphere

Sperber saw in Hopper's Coast Guard Station a provocative, binary interplay of geometric (architecture) and organic (ground and rocks) elements. Her re-envisioning of the painting divided it into four quarters, top right and left and bottom right and left. Making four replications of each of the quarter sections, she formed four new compositions from the painting's quadrants. Two resulting compositions of the organic/ground and rocks elements resemble Southwest, Navajo textile designs and the other pair, based on the upper architectural sections, become quasi-surreal landscapes. Hopper's decidedly American landscape has been turned in four very modern, tapestry-like, abstract compositions. The four-segmented versions, along with her replica of the original Hopper composition, are fashioned from chenille stem/pipe cleaner elements. This favored medium of childhood creativity was chosen for its wide range of colors and sharp end of each stem, which became the pointillist pixels that realized Sperber color-charted and graphed detailed computer-based printout. All five of her textile versions of the Hopper's Coast Guard Station float horizontally above a vinyl wall covering that smoothly covers the upper part of the twenty-two by thirty foot expanse of the Laurie Foundation Art Stairway's back wall. Using the artist's digital file, the vinyl backdrop was commercially imprinted with repeated banded sequences of the four quartered, rotated, and flipped Hopper elements, the two Southwest Native American textile-like motifs were positioned vertically and the architectural elements are likewise rotated into a vertical position in contrast to the horizontal placement of the big, pipe-cleaner panel versions. At first glance it may be hard to see that these textured and flat images are the same, as well, while the bands of repeated, similar motifs have the same width, one of the architectural element motifs looks wider. The scale, material, and surface distinctions transform the perception of the motifs in subtle yet potent ways. The overall results for Sperber are "as much a mixture of tropes of American and 'Native American' art as western culture's elevation of high art and degradation of low art." Scale disjunctions from the chenille stem panels and the minute and more muted imprinted vinyl wall covering turn a staple realist image into an abstraction and one of the Museum's American art highlights into four not immediately recognizable, abstracted compositions. Quartered, Flipped, and Rotated connects the Museum's two primary collection areas, American and Native American art, in utterly unexpected and novel ways that add powerful cross-cultural insight and interplay into Sperber's ambitious artistic sensibility and production.

Curator of the exhibition

Director, Montclair Art Museum

*The artist's quotes and statements came from a series of e-mail exchanges and conversations in June and July 2004 between the artist and Patterson Sims, Director of the Montclair Art Museum and curator of the exhibition.

McKenzie Fine Art, Inc., New York represents Devorah Sperber.

The vital assistance on this project of Montclair Art Museum staff members Pia Babendure, Charles Cobbinah, Michelle Grohe, Toni Liquori, Anne-Marie Nolin, Renee Powley, Jason Van Yperen, and Joseph Zadroga is acknowledged with appreciation. Thanks also to Lawrence Aufiero of Project Sign for his company's work on the vinyl wall covering.

All Montclair Art Museum programs are made possible, in part, by the New Jersey State Council on the Arts/Department of State, a Partner Agency of the National Endowment for the Arts and funds from the National Endowment for the Arts; Judy and Josh Weston; the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation; and Museum members.

Quartered, Flipped, & Rotated

detail views of five chenille stem work