Sculpture Magazine

Feature Article

May 2006 Issue

"The

Art of Seeing"

A Conversation with Devorah Sperber

by Ana Finel Honigman

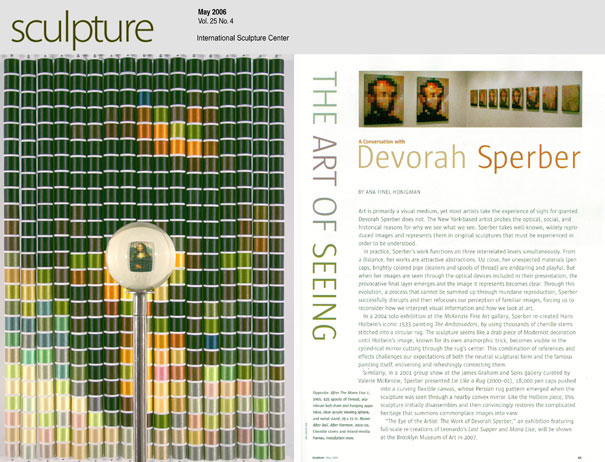

After The Mona Lisa 1, 2005. 425 spools of thread, aluminum ball chain, stainless steel hanging apparatus, clear acrylic viewing sphere, and metal stand, 29 x 21 in.

page 48

After Dali, After Harmon, 2003-04. Chenille stems and mixed media frames, installation view.

Art is primarily a visual medium, yet most artists take the experience of sight for granted. Devorah Sperber does not. The New York-based artist probes the optical, social and historical reasons for why we see what we see. Sperber takes well-known images that are widely reproduced and represents them in an original sculpture which must be appreciated visually in order to be understood. In this way, she undermines the process Walter Benjamin claimed corrupts art's authenticity and kills its 'aura' in the age of mechanical reproduction.

In practice, Sperber's work functions on three interrelated levels simultaneously. From a distance, her works are attractive abstractions. Up close, her unexpected materials (pen caps, brightly coloured pipe cleaners and spools of thread) are endearing and playful. But only when her images are seen through the optical devices she includes in their presentation does the provocative final layer emerge and the image it represents become clear. Through this evolution, a process that can not be summed up through mundane reproduction, Sperber successfully disrupts and then refocuses our perception of familiar images; forcing us to reconsider how we interpret visual information and how we look at art. In a 2004 solo exhibition at the McKenzie Fine Art gallery, Sperber recreated Hans Holbein's iconic 1533 painting, The Ambassadors, by using thousands of chenille stems stitched into a circular rug. The sculpture seems like a drab piece of modernist decoration until Holbein's image, known for its own anamorphic trick, becomes visible in the cylindrical mirror cutting through the rug's centre. This combination of references and affects challenges our expectations of both the neutral sculptural form and the famous painting itself, enlivening and refreshingly connecting them.

Similarly, in a 2001 group show at the James Graham and Sons gallery curated by Valerie McKenzie, Sperber presented Lie Like a Rug (2000-2001), 18,000 pen caps pushed into a curving flexible canvas, whose Persian rug pattern emerged when the sculpture was seen through a nearby convex mirror. Like the Holbein piece, this sculpture initially disassembles and then convincingly restores the complicated heritage that summons commonplace images into view.

"The Eye of the Artist: The Work of Devorah Sperber," an exhibition featuring full-scale re-creations of Leonardo's Last Supper and Mona Lisa, will be shown at the Brooklyn Museum of Art in 2007.

page 49

Reflections, 2003-04. 60,000 spools of thread and 23 convex mirrors, each wall 10 x 60 ft. View of work installed at the Centro Medico Train Station, San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Ana Finel Honigman: How does the process of visually dissecting and reconstructing historical works of art affect your relationship to them as a viewer?

Devorah Sperber: My artistic process is highly compartmentalized. It includes countless hours of research, planning and preparation, which affect my relationship to both the historical work and the resulting new work. Once assembly begins, I'm already finished in a sense, with most of the decisions and problem solving behind me. At this point I have such a clear vision of the completed work in my mind, that when I first see the finished work, I have a strange sense of Déjà vu." This was particularly poignant when I recently installed "Reflections," a large-scale commissioned work constructed from 60,000 spools of thread, in a train station in Puerto Rico. After working on the project for 15 months, I could not see it with "fresh eyes" and had to assess the work by gauging other people's responses to it.

AFH: How do you think this experience would differ if you were appropriating these works in paintings or collages instead of translating them from two-dimensional images into sculpture?

DS: I don't think of my series based on historical works as appropriation. The catalyst was a site-specific installation, "Quartered, Flipped, & Rotated" (2004), which I developed for the Montclair Art Museum two years earlier. Curated by Patterson Sims, the installation was based on the museum's iconic Edward Hopper Painting Coast Guard Station (1929) and connected the museum's collection of American and Native American holdings. My decision to use other historical works as subject matters evolved from my interest in the link between art and technology through the ages, and my own working processes, which utilize technologies of our era--the computer, optical devices, and mass-produced objects. The selected historical works have significant links to science or technology (some well known, others obscure). I focus on those aspects when translating images into new sculptural works.

AFH: How are you defining appropriation and how does your use of pre-existing imagery differ?

DS: In the context of visual art, I define appropriation as "art about art." My work focuses on the intersection of art, science, and technology and their influence on "the art of seeing." AFH: What is the "art of seeing?" Do you mean the way viewer interpretation affects the meaning of a work?

DS: I am interested in how the human brain makes

sense of the visual world and "reality" as a subjective experience. As a visual

artist, I cannot think of a topic more interesting and yet so basic than the

"art of seeing."

AFH: Your series After Dali, After Harmon 1, 2003-2004 was inspired

by a known experiment on optics and memory. Can you describe the particulars?

DS: This series was based on a Salvador Dali painting from 1976, which was based on an early pixilated image created by Leon Harmon of Bell Labs. The original black and white image was included in an article in a 1973 issue of Scientific American, titled "The Recognition of Faces." The image and the experiment was a demonstration of the minimum conditions needed to recognize a face. Through the use of incremental cropping and changing scale, the series "After Dali, After Harmon" takes it one step further. When seen in its entirety, the series functions as a neurological primer, literally priming the brain to make sense of visual imagery, which is only recognizable when seen in the context of the greater whole.

page 50

Shag Rug 165,000 (After Pollock), 2002. 165,000 2-in. chenille stems and foam board, 96 x 192 x 3 in.

AFH: How does your work relate to the experience of seeing in contrast to say, a painting dealing with similar issues, such as a Chuck Close's grid portrait?

DS: Chuck Close's grid portraits are installed in a traditional way, first offering viewers an overview of the portraits from a distance, with the image gradually dissolving into abstract cells as they move closer. My large-scale works reverse this traditional process of viewing art, bypassing the overview or macro-perspective and offering in its place an incomprehensible micro-perspective of individual units (such as spools of thread) devoid of recognizable imagery. Viewers experience a dramatic moment of surprise when they become aware of the macro-view, visible only with the aid of small optical devices. This element of surprise, best described as the "WOW" experience, is the result of temporal lobe activation, which occurs when the external world does not jive with the brain's inner expectation.

AFH: What issues arise from offering the experience of seeing the same thing in two separate and distinct ways through the use of sculptural elements?

DS: Offering two distinct versions of reality illustrates the limitations of visual perception and presents reality as a subjective experience vs. an absolute truth. It demonstrates that the visual world, as perceived by the human eye and brain, consists of a miniscule layer of scale-based perception existing within infinite layers of imperceptible realities.

AFH: What do you think of how your sculptures appear in photographs?

DS: It is difficult to accurately portray my work with a single photographic image. I generally prefer a combination of images: a close-up view, a full installation view, and/or a view of the work as seen reflected in an optical device. Sometimes, a mid-range view is necessary to link the micro and macro views, especially when people have not seen my work in person. The size of the photograph is also important as it affects whether the focus is on the full recognizable image or on the individual units.

AFH: How do you select the images you reference?

DS: My initial interest in any subject matter is intuitive. I then conduct research to access whether the subject matter has enough interesting layers to justify producing a work based on it.

AFH: When you say "layers" are you referring to content, like the potential socio-political content in a mass-produced oriental carpet or the historical content of a famous painting or are you describing visual variety?

DS: Selecting my subject matter is a complicated process. After I find a group of images that appeal to me on an intuitive level, each image undergoes a rigorous justification process. I am looking for a reason to pursue one idea over others.

AFH: Does the familiarity viewers might have with a work affect the way you conceptualize and contextualize it?

DS: Most of my work is accessible to both the art-going and general public. However, in some cases, if viewers are familiar with the subject matter, they will likely appreciate additional layers of meaning. For example, viewers familiar with Jackson Pollock's work will appreciate the humor intended in recreating a drip painting using 165,000 pipe cleaners. What they may not know is that in each successive drip painting, Pollock created higher and higher ratios of fractals, before fractals were recognized as existing in the natural world. This was a deciding factor in using Pollock's Autumn Rhythm as a subject matter.

page 51

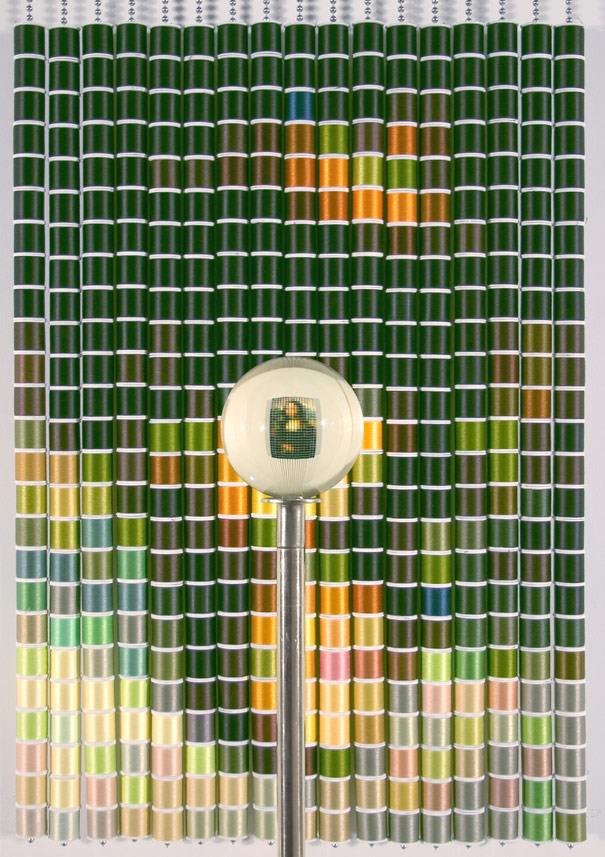

After Holbein, 2003-04. Chenille stems, mixed-medium platform, and polished stainless steel cyinder, 76 x 76 x 31 in. After Holbein (skull), 2003-04. Chenille stems and mixed-media frame, 18.5 x 103 x 2 in.

AFH: How do you feel the meaning or significance of an image changes when it is frequently reproduced?

DS: Reproductions of historical works can become inaccurately fixed in the mind's eye. Take the Mona Lisa for example, perhaps the most famous painting in the world. Most people have seen a reproduction or a "reproduction of a reproduction," but only a small percentage of those people has actually seen the painting in person. I suspect most people are surprised when they see the original painting and experience the relatively small scale (30 x 20 7/8") and the subtle effects of Mona Lisa's elusive smile. I am currently working on a life-sized rendering of the Mona Lisa. Constructed from only 425 spools of thread, the image resolution will be extremely low. Yet when seen with an optical device, the thread spools will condense into a blurred yet recognizable image, conveying how little information the brain needs to make sense of visually imagery, like Harmon's pixilated image of Lincoln. Another larger thread-spool work will reintroduce an aspect of the original painting which is absent in most reproductions-the effects of spatial frequencies on vision as it relates to Mona Lisa's elusive smile. These works will debut in Ljubljana, Slovenia, in June 2005 in an exhibition curated by Marilyn Kushner of the Brooklyn Museum of Art, who is interested in the intersection of digital technology and printmaking.

AFH: What are the differences for you between creating a work from the image of a factory-made carpet versus reconfiguring Holbein's The Ambassadors?

DS: I don't see a significant difference. Both works have links to technology. "Lie Like a Rug" was inspired by a rug which has been in my family since the 1950s. My research uncovered an interesting technological fact about the origin of that particular rug pattern. Although it looks like a hand-made Persian rug, the pattern is modeled after the world's first power-loomed rug manufactured by Karastan in the USA continuously since 1928.

AFH: And the Holbein?

DS: Two works titled "After Holbein" were based on Hans Holbein's painting The Ambassadors (1533). In order to create the elongated skull, Holbein either utilized anamorphic perspective, a mathematical technology invented by Leonardo da Vinci, or an optical device as suggested by David Hockney in his book "Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters." These works debuted at McKenzie Fine Art, NYC in 2004 in an exhibition that included a thread-spool work based on Vermeer's presumed use of the camera obscura and the series "After Dali, After Harmon". All of these works have a significant link to technology.

AFH: How has your process changed since when you began using technology in your work?

DS: At the beginning, I spent weeks translating images into individual units of color. I now have a custom software program that reduces the time I spend at the computer and allows me to spend more time in the studio.

AFH: As your work demonstrates, science and art are closely linked, and always have been, yet there is a general assumption that science is not creative and art is not as "serious". Why do you think there is still a division perceived between science and art?

DS: The modern division of art and science may be the result of technological advancements and resulting job specialization. Intuition/creativity and awareness of the world play important roles in both art and science. If there is a perception that art isn't as serious as science, it may be due to science's more tangible value to society.

AFH: So, you are focusing on seeing as it functions biologically instead of intellectually, since one could argue that the subjective experience of seeing is determined more by experience, information and assumptions than optics?

DS: I like the holographic model of reality in which raw perceptual data is input, filtered, and organized by the brain to create a holographic illusion of a solid, predictable universe. Our understanding of what we see is based on the holographic model we have built to date. Using this model, brain biology and function are interconnected.

page 52

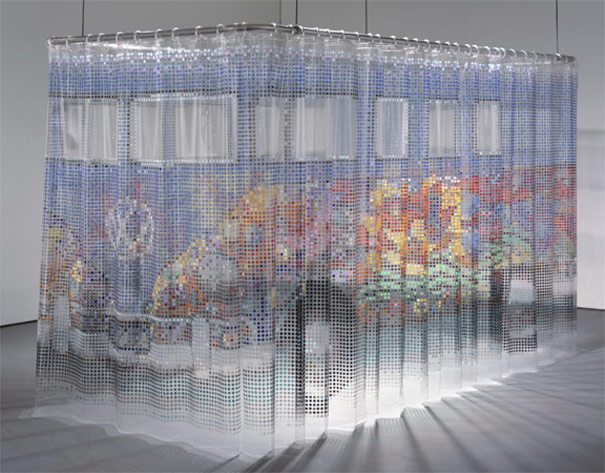

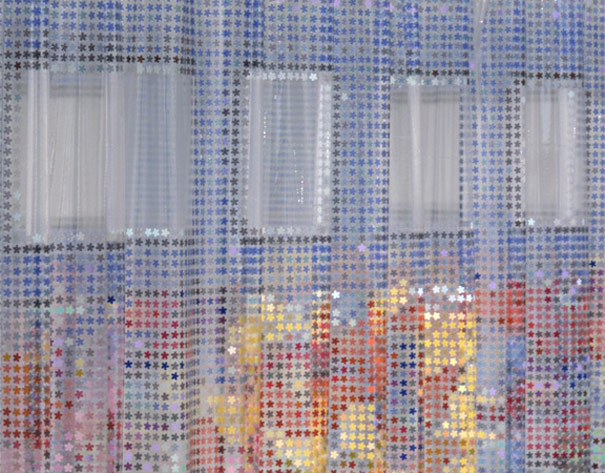

VW Bus: Shower Power, 2001. 60,000 colored film stickers on vinyl shower curtains, aluminum hanging apparatus, and convex mirrors, 80 x 63 x 136 in.

AFH: Would you say that you approach the actual act of making your sculptures scientifically?

DS: My approach to research and development can be seen as scientific but the actual assembly process is totally meditative. Assembly is my delayed gratification for the countless hours spent thinking, researching, planning, and problem solving. Life doesn't get more simple then declaring "I will complete X number of rows today" and having the wherewithal to do it.

AFH: Why do you often select mediums that are often banal or playful in their origins, like thread or brightly colored pipe-cleaners?

DS: The contrast between subject matter and medium adds another element of surprise to the work. In general I select materials based on their aesthetic qualities, intrinsic characteristics, availability, and the range of colors. I place equal emphasis on the "whole" recognizable image and how the individual parts function as abstract elements.

AFH: Yet, sometimes your materials conceptually compliment your subject matter like when you crafted a life-size replica of a 1967 VW bus using over laser-cut 60,000 flower-power stickers, hand-applied onto clear vinyl shower curtains. At other times, your choice of material and scale is highly incongruous. What determines whether you want your medium to contrast or reinforce your subject's symbolism?

DS:"VW Bus: Shower Power," a life size, 3D rendering of a 1967 VW Bus, was inspired by my long-standing love of VW buses and my own retro VW Bus. My choice of medium, 60,000 flower-power stickers applied onto clear vinyl shower curtains, was inspired by the common description of a VW Bus as a "box on wheels." When viewed up-close, the translucent flowers in the foreground fade in and out of recognition as the eyes shift focus from the front panels through to the rear panels on the opposite side of the bus. The end result is an image of a VW Bus that is there yet not there, solid yet transparent, present yet fleeting, not unlike the ideals of the 60s in the minds of many Baby Boomers today.

AFH: What was it about the myth of the 1960s that inspired that exhibition?

DS: "Bikinis, Bandanas and a VW Bus" debuted at Graham Gallery in NYC in March 2002. The concept was based on the continuing presence of cultural icons from the 1960s and 70s. As David Brooks has noted in his book, Bobos in Paradise, these icons continue to have a strong presence in contemporary culture due to the influence of "Counter-Culture Capitalist" baby boomers now in positions of power as CEOs, advertising executives, and designers.

AFH: How did you try to represent the tensions between 1960's ideology and the current aestheticization or commercialization of those beliefs?

DS: The bikinis and bandanas were constructed from thousands of maptacks inserted in clear vinyl, and have an undulating, cloth-like appearance from a distance and a surprisingly menacing quality up close. At first glance, all of the works appear to be 3D but on closer inspection, some are actually 3D while others are entirely flat. The bikini patterned as the American flag first emerged in popular culture during the 1970s. Seen today, it can be read as either patriotic or subversive depending on the direction of the maptacks which face inward on some bikinis and outward on others and also, of course, on the perspective of the viewer .

Ana Honigman is a critic and PhD candidate in art history at Oxford University

page 53